Patrice Higonnet, Paris: Capital of the World

Nostalgia for an Older Paris and the Political Right

AT FIRST this counter-myth of old Paris was politically .innocuous. For writers like Hugo and Nerval, the defense of old Paris was a literary phenomenon, even an emotional necessity, but not a political or sociological issue. Things stayed that way until about 188o, when suddenly everything changed.

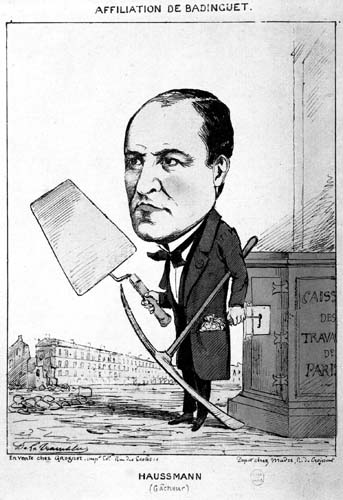

Now everyone came to understand that the real Paris, the Paris of Haussmann or the revolutionaries, had been the ideologized expression of a political will to change, to modernize, to "Americanize," to accept a bourgeois present and perhaps also a mildly democratic future. The demolition of an aging, sordid city had represented -- they now understood -- the"irresistible march of progress." . . . .

Afrer 1880, however, public opinion shifted somewhat in the opposite direction. For a new Parisian right, which was soon to become populist or Boulangist and which in some respects was the precursor of twentieth-century fascism, the cult of old Paris ceased to be merely a romantic gesture, as it had been for Hugo, the apostle of progress and republicanism. Henceforth the nostalgia for old Paris was to be one of the new right's most powerful weapons in the war against the party (or parties) of the Enlightenment -- parties of the revolutionary or socialist left and the capitalist, Haussannian center.

Haussmann and modernization: for some these terms now became synonymous with capitalism, Jews, and money: ''The more I study the eighteenth century," Jules de Goncourt wrote in 1861, "the more I see that its principle and purpose was amusement, pleasure, just as the principle and purpose of our century is enrichment, money ... Life in the eighteenth century was for spending money. Modern life is for amassing it."

The great predecessor of this new sensibility was undoubtedly [the mid-19th century novelist Honoré]Balzac the inspired -- and reactionary -- enemy of modernity and industry. "In working for the masses," he wrote, "modern industry goes about destroying the creations of ancient Arr, whose works were as personal to the consumer as they were to the artisan."

Then, in 1867, came Louis Veuillot, an ultra-Catholic pamphleteer and an unconditional admirer of Pope Pius IX. What did modern Paris -- or, to borrow the title of Emile de Labedolliere's 1861 guide book, "the new Paris" -- mean to a man like Veuillot? The answer is clear:"City without a past, full of minds without memories, hearts without sorrows, souls without love! City of uprooted multitudes, shifting piles of human dust, you can grow to become the capital of the world, [but] you will never have citizens ... Who will live in his father's housewho will pray in the church where he was baptized? Who will know the room in which he first heard a child's cry or gathered in a final sigh? ... My house has been torn down, and the earth has swallowed it up … The ignoble pavement has covered everything."

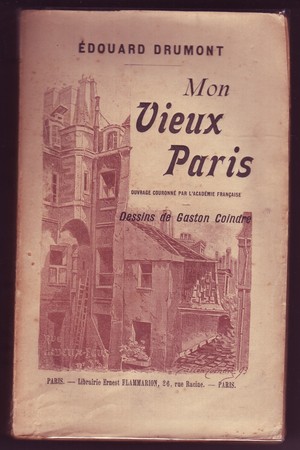

And after these premonitory signs came a flood that began with Edouard Drumont, one of the prime movers behind populist anti Semitism in France. . . . Drumont's book Mon vieux Paris [My old Paris]first published in 1878, was quite restrained. . . .

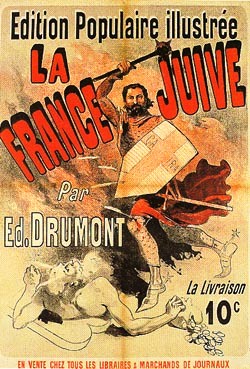

By contrast, the 1893 edition of the same book was ferocious. The myth of old Paris was no longer just a pleasant dream: it had become a political weapon. What was modern, Haussmannian Paris? The distillation of a poison called the "Parisine," an "exquisite and lethal essence ... a subtle poison." Drumont had recast his argument in resolutely anti-Semitic, xenophobic terms. Paris was a new Babylon, the capital of "European interlopism." It stood for rootlessness, noxious foreigners, and "Jewry."

Edouard Drumont's Anti-Semitic Journal