T.J. Clark, The Painting of Modern Life

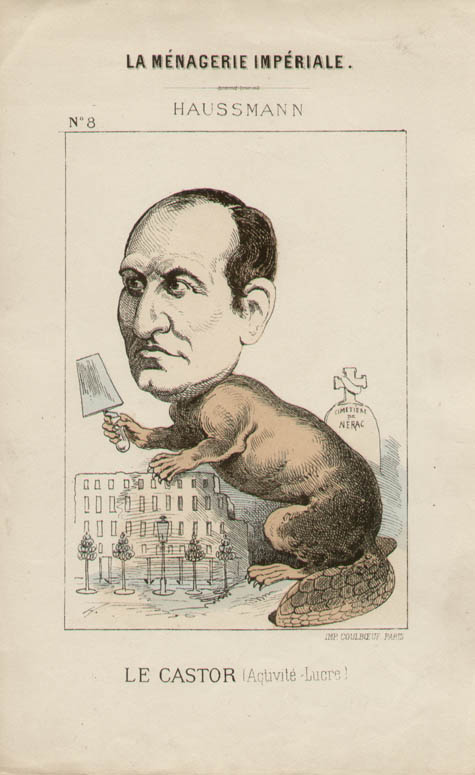

A Cartoon from the 2nd Empire: The Imperial Menagerie -- Haussmann, The Beaver (Lucrative Activity)

the houses in which they were found; and on one ladder I saw a well-dressed bourgeois [member of the middle class]effacing the street name of the Boulevard Haussmann, and substituting that of 'Victor Hugo.'” One month later, when the mob first invaded the Hotel de Ville, there was some of the same symbolism: ''Furniture is smashed. A splendid plan of Paris, drawn up by Haussmann's engineers and Napoleon's Haussmann, is cut to pieces by the vengeful Reds. They break into the chamber where the twenty mayors are in session. The mayors flee."

Time and again one is struck by the vehemence and diversity of and diversity of opposition to the new city: vengeful Reds and well-dressed bourgeois in temporary agreement as to what they had suffered at whose hands. It is often hard to make out what the agreement derived from: what was it exactly that so little endeared Baron Haussmann to his fellow citizens, and persuaded them that public works were the worst part of empire?