Ann-Louise Shapiro, Housing the Poor of Paris, 1850-1902

With the rebuilding of the city, the administration succeeded in converting Paris from a medieval city into an  imposing capital. Applying on an unprecedented scale "the surgical method to the treatment of a sick city," Napoleon and Haussmann demolished slums and drove broad boulevards through congested areas of the center, opening up corndors of light and air. They improved circulation with a coordinated network of roads which simplified communication within the city and mcreased access both to the central markets and to the railway terminals on the outsktrts. The addition of a major system of collector sewers and an enlarged supply of spring water enhanced public health and reduced the incidence of cholera. They embellished the city with public parks, landscaped squares, and gran diose monuments. Invoking the accepted remedy of the ttmes, Napoleon and Haussmann used public works to eliminate some of the most hghly visible afflictions of the urban environment.

imposing capital. Applying on an unprecedented scale "the surgical method to the treatment of a sick city," Napoleon and Haussmann demolished slums and drove broad boulevards through congested areas of the center, opening up corndors of light and air. They improved circulation with a coordinated network of roads which simplified communication within the city and mcreased access both to the central markets and to the railway terminals on the outsktrts. The addition of a major system of collector sewers and an enlarged supply of spring water enhanced public health and reduced the incidence of cholera. They embellished the city with public parks, landscaped squares, and gran diose monuments. Invoking the accepted remedy of the ttmes, Napoleon and Haussmann used public works to eliminate some of the most hghly visible afflictions of the urban environment.

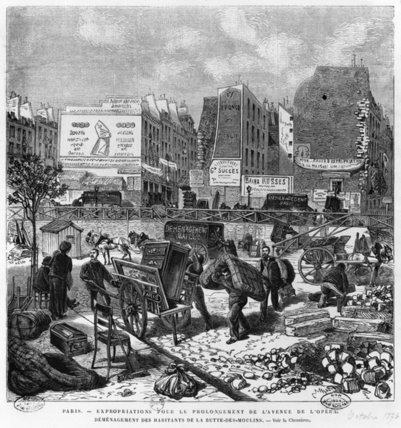

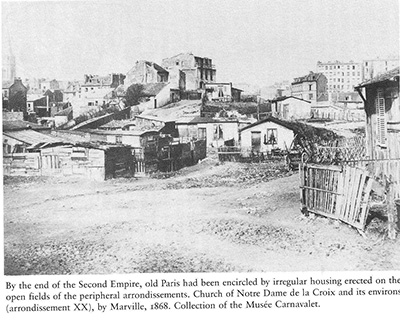

But public works could not fulfill the extravagant expectations which they raised. Although some of the worst slums were cleared away, broad boulevards and open spaces created an illusion whtch belied the reality. The demolition of groups of houses produced increased crowdmg m the remaining buildings as residential locations were converted into streets and open squares. The added elegance of the center ( today's gentriftcation) accelerated the geographic polarization among the classes, forcing the poor to migrate to the southern and eastern periphery. In spite of the incorporation of the suburban communes into the city proper in 186o, Napoleon and Haussmann neglected to provide comparable services to these annexed territories. Problems of overcrowding, shoddy constructions for the poor, and the geographical separation of the social classes did not begin with Napoleon and Haussmann; these problems were nevertheless intensified by the scale of redevelopment during the Second Empire. In the end, the grand enterprises of this period shifted the geographic locus of urban problems, particularly those of the working classes, but did not solve them. The social and material consequences of the rebuilding of Paris instead created the framework in which contemporaries struggled with the issue of workingclass housing for the remainder of the century. . . .

The extent of Haussmann's demolitions for street improvements and the increased value of the new constructions combined to produce a significant upheaval in the availability of inexpensive lodgings. As the population of Paris increased by 261,549 between 1851 and 1856, swelled largely as a result of in-migration, the number of houses actually decreased from

30,770 to 30,175. Critics of the public works programs pointed to the

growing incongruity between the diminishing housing supply and the thousands drawn to Paris by the promise of work in the building trades. Haussmann countered with the claim that although 25,562 individual lodgings disappeared in the period 1852-59, new constructions provided an additional 58,207 lodgings, a net gain of 32,645.He estimated that117,552 families, or about 35o,ooo persons, had been displaced as a result of demolitions, but considered this dislocation insignificant in light of the larger benefits provided by public works, In response to critics, Haussmann sanguinely noted that it is not possible to accomplish this transformation without creating a general upheaval, the necessity of which cannot be appreciated by the masses, who become easily wearied, especially when [the upheaval] is prolonged for seventeen years." Beyond the raw statistics, it is more important to assess the change in the relationship between the number of inexpensive dwellings and the size of the working class population. Haussmann's policies are less benign when seen from this vantage point. The number of workers rose from 416,000 in 1860 to 442,000 in 1866, an increase of 25,000, with up to 70,000 seasonal workers at a given period. At the same time the number of rents below Fr 250 increased more slowly: 101,909 in 1863; 104,619 in 1865; 114,169 in 1866.

The extent of Haussmann's demolitions for street improvements and the increased value of the new constructions combined to produce a significant upheaval in the availability of inexpensive lodgings. As the population of Paris increased by 261,549 between 1851 and 1856, swelled largely as a result of in-migration, the number of houses actually decreased from

30,770 to 30,175. Critics of the public works programs pointed to the

growing incongruity between the diminishing housing supply and the thousands drawn to Paris by the promise of work in the building trades. Haussmann countered with the claim that although 25,562 individual lodgings disappeared in the period 1852-59, new constructions provided an additional 58,207 lodgings, a net gain of 32,645.He estimated that117,552 families, or about 35o,ooo persons, had been displaced as a result of demolitions, but considered this dislocation insignificant in light of the larger benefits provided by public works, In response to critics, Haussmann sanguinely noted that it is not possible to accomplish this transformation without creating a general upheaval, the necessity of which cannot be appreciated by the masses, who become easily wearied, especially when [the upheaval] is prolonged for seventeen years." Beyond the raw statistics, it is more important to assess the change in the relationship between the number of inexpensive dwellings and the size of the working class population. Haussmann's policies are less benign when seen from this vantage point. The number of workers rose from 416,000 in 1860 to 442,000 in 1866, an increase of 25,000, with up to 70,000 seasonal workers at a given period. At the same time the number of rents below Fr 250 increased more slowly: 101,909 in 1863; 104,619 in 1865; 114,169 in 1866.

The numbers of individual lodgings did not, moreover, necessarily indicate better living conditions. It is likely that in increased number of separate reflected the breaking up of old apartments into smaller units as well as actual new constructions . . .