Patrice Higonnet, Paris: Capital of the World

Nostalgia for the Old Paris

IN 1851 Theophile Gautier railed against the vestiges of medieval Paris: "Three-quarters of the streets are nothing but rivers of black and putrid muck, as in the days of outright barbarity." What most struck him about the demolition work undertaken by Haussmann was "all the ugliness" it revealed: ''One had no idea how hideous Paris was, for so much was carefully hidden away behind its boulevards, its river, and its fine streets. It is only after visiting the cesspools laid bare by the new construction that one becomes convinced of the need for all this work, which is turning the city upside down to good purpose and mak ing a home for civilization."

Within thirty years, however, a reaction would set in (and I use the word "reaction" advisedly): a new myth of Paris would overturn the modernizing myth that had shaped Gautier's perception. Arrayed against the liberal, Haussmannian myth of Paris, capital of modernity and of crime, there now arose the counter-myth of "old Paris." In I840 old Paris seemed repellent. By 1890 it had become quite charming, rather surprising everyone, including Haussmann, who said of this new mood and of its votaries that "it is now fashionable to admire old Paris, which they know only from books"-a point of view that surprises us today, in turn, because we too are moved by the Paris of the past that Haussmann so disdained. We are glad that of all the cities of the world, old and new, Paris is the one that has taken the best care of its architectural and monumental past.

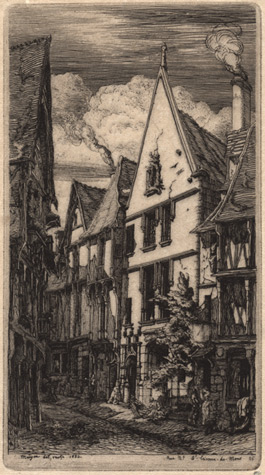

Engraving of the Les Halles Region of Paris Before Haussmann's Changes by Charles Meryon (1821-1868)

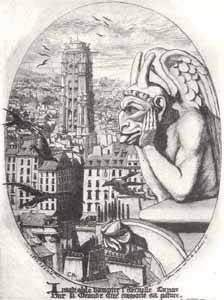

Meryon's Engraving of the view from the top of Notre Dame.

. . . [Victor] Hugo's premier contribution to the history of the city was the reinvention of its past when he published his first great novel, Notre-Dame de Paris. [Usually translated into English as The Hunchback of Notre Dame] Old Paris was not just a setting for Hugo's novel. He now made of it an organic entity, a living organism, whose future should be a function of its past, an idea that he illustrated with a profusion of Parisian metaphors: the city was a "forest of steeples, of turrets, of chimneys"; in Paris, "buildings ... have their own way of growing and spreading ... they shoot up like pressurized sap."

Notre-Dame de Paris was an event in the history of the city, and in its wake a host of neo-Romantic writers set out to counter the rival myth of "laboring classes/dangerous classes." Instead of a Paris beset by crime and wallowing in filth, one now had a picturesque Paris, a city that was a work of art or at any rate a strange and wonderful thing, an organic whole; and Hugo's use of such metaphors proved contagious.

Alexandre Dumas, for example, in his Isabelle de Bavière, has two characters contemplate the city from atop a tower of the Bastille. They see "an indistinct mass of houses stretching from east to west, whose roofs seemed to run together in the dark like the shields of an army on the march." In his Fragments de Nicolas Flame!: Drame chronique. Gerard de Nerval climbs the Tour Saint-Jacques in order to take in all of Paris at a glance: "How high this tower is! The higher I climb, the more the things of the earth seem to fall away like mist. Paris ... all Paris is there, wirh irs dais of haze ripped by a thousand needles ... And what if I were ro dive from here into those waves of roofs and belfries?". . .

Many other writers, such as Alfred des Essarts, Louis Bouilhet, and Victor Fournel, followed suit and wrote copiously not only about the charms of old Paris but also about the brutality of Haussmann's project. Haussmann here was a kind of villain; in 1856 a German observer by the name of Adolf Srahr accused "the new master of Paris'' of wanting to destroy the old city altogether, and in that same year the poet Charles Valette called Haussmann a "cruel demolisher":

Je cherche Paris en vain

Je me cherche moi-meme ...

(I search in vain for Paris

I am searching for myself .. .)''

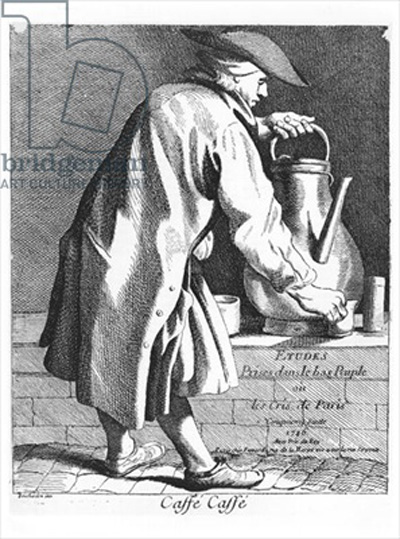

Engraving of the Seine in earlier times by Charles Meryon.

From year to year, more and more Parisians were moved by this new nostalgia. Now people began to weep for old Paris, with its placarded walls and noise-filled streets, which Edmé Bouchardon had captured in his eighteenth-century engravings. They sighed for Paris as a whole and for each of its neighborhoods taken one by one, forgetting even then what we still forget today: that compared with the great cities of northern Europe, the four arrondissements of central Paris had suffered rela tively little. For many, each neighborhood became a city unto itself, indeed a separate country, with its own customs, manners, languages, signs, and markets. . . . In 1854 the writer Alexandre Privat d'Anglemont declared: “What is wonderful about Paris is that the customs of the people who live on one street are no more like the custom’s of the people who live on the next street than the custom’s of Lapland resemble those of South An1erica ... It is this constant kaleidoscope that is so charming to observe. . . ."

"If no other city offers more striking or more agitated lives," explains Emile Souvestre in Un Philosophe sous les toits (A Philosopher in the Attic), a work to which the Academie awarded a prize in 1851, "neither does any other city offer lives more obscure or unperturbed. Big cities are like the sea: as you descend toward the bottom, you come upon a region inaccessible to bustle and noise."