Questioning Haussmann's Revolution

Joan DeJean, How Paris Became Paris (New York, NY : Bloomsbury, 2014), pp,17-19.

In her study of Paris in the 17th and 18th century historian Joan DeJean has argued that the "rationalization" of the streets of Paris was already in place long before Haussmann made his contribution to the process in the 1860s and 1870s. Here is a brief presentation of her position.

Today, one individual is often seen as single-handedly responsible for the modernization of Paris' cityscape and the

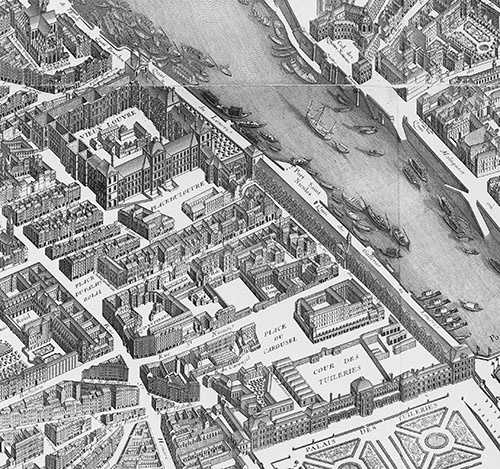

1739 Map of the Louvre and Tuilleries Palaces |

creation of its most iconic features: Baron Georges Eugene Haussmann. Those who now give Haussmann exclusive credit for having brought Paris into the modern age often add that Paris in the mid-nineteenth century still had the aspect of a medieval city.

The redesign that was carried out under Haussmann's direction in the mid nineteenth century did replace some medieval streets with a network of boulevards; following a plan based on straight lines and geometric precision, it remade a significant section of the city. It was, however, merely the second of two great periods of building that transformed medieval Paris into the city we know today. Those who give Haussmann sole responsibility for the modern face of Paris fail to recognize that the vision of urban modernity now associated with his name had in fact become characteristically Parisian two centuries earlier. Haussmann was in large part following a template established by those who reinvented Paris in the seventeenth century.

When Haussmann began his work, the vast sections of the city that had been added between 1600 and 1700 were in no way medieval. In these parts of Paris, urban modernity already loomed large, in the form of the original grand boulevards, of broad and straight thoroughfares, of streets designed to open up the city and make travel through it easy. For example, when Haussmann razed all existing construction on the Ile de la Cite, he largely spared the island next to it: the Ile Saint-Louis featured grid planning and residential architecture dating from the seventeenth century but already fully up to nineteenth-century standards.

In similar fashion, the phenomena that developed on the new boulevards of nineteenth-century Paris and that are seen as inherently Parisian experiences -- department stores and omnibuses, cafe culture and bright lights -- all first became available to Parisians and visitors in the seventeenth century's final thirty years, as soon as the city's original ring of boulevards began to be traced. By then, the first decades of planned development in its history had changed the city more quickly than ever before. Paris had already become what Claude Monet referred to in 1859 as "cet étourdissant Paris," "that dizzying" place, a "whirlwind" of seduction that, Monet added, "causes me to forget basic obligations."

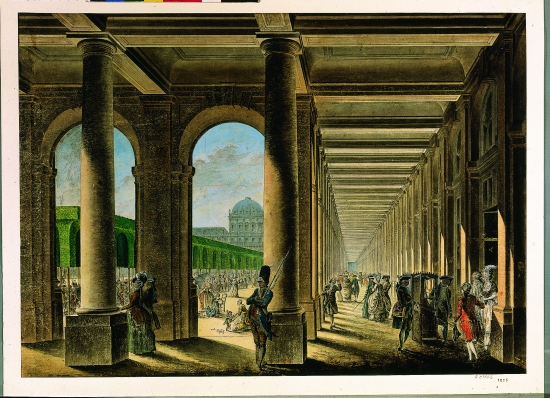

The Palais Royal in the 18th Century