Raymond Rudorff, Belle Epoque

French Attitudes Towards Sexuality in the late 19th Century

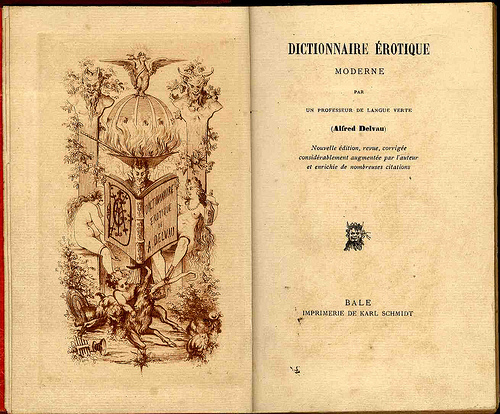

Afred Delvau Dictionnaire érotique moderne (1864)

and collectors, most of the pseudopornographic "yellow-backed" novels that were available to foreign tourists in Paris were naïve and repetitive. The "daring French novel" that the English or American tourist brought back in his suitcase as evidence of French lubricity might either be a genuine work of literature by one of the "realist" or "decadent" writers or a titillatory saga of the cavortings of a wealthy and eccentric "milord" among an assembly of heartless governesses or exotic female flagellants. Although such books flirted with taboo subjects, in their style and attitudes they were not so very different from the more respectable and worldly novels of "Gyp" and Paul Bourget who wrote of adultery and seduction and gave their theme a veneer of superficial "psychology". Nonetheless, the fact that adultery featured so conspicuously in French plays and novels convinced many foreigners that Paris seethed with immorality and was a haven for the debauchee.

By the second half of the 19th century, French writers had been dealing with sex with increasing frankness, often in the name of "realism" which could represent an ideology, a crusade and a literary movement. But each victory of the realistic school was generally only won after a battle. The difference with the more hypocritical and prudish Anglo-Saxon world was that at least it was possible to give battle in the first place. Emile Zola's novels were attacked in England as disgusting but his novels together with such naturalistic works as Goncourt's Elisa,several of Maupassant's tales and even Flaubert's Madame Bovary had not gone unassailed in France. The movement towards freedom in literature gained impetus steadily towards the end of the century and its reverberations abroad had, at one level, given a picture of a remarkably cynical and amoral society.

France was a secular republic without a royal family to give an example of middle-class stability and respectability. The church was open to violent attack and even persecution, and a popular cynicism, encouraged by a century of political turbulence and scandals, encouraged the man in the street to regard immorality in high places as a matter of course. But as far as the almost legendary French amour went, the belle époque was only belle for a small minority. A dedication to eroticism, adultery and illicit love was not for the bourgeois and if we read such popular novels as those of Paul Bourget, the writer of the "Physiology of modern love", we have the impression that such "modern" love was reserved for the upper strata of society--a luxury for the happy few like cordon bleu cuisine. Paris was certainly less puritanical in the Nineties than England or the United States but, even so, tolerance had its limits. Oscar Wilde would not have been prosecuted in France but it is significant that during his brief stay in Paris after his imprisonment he was never taken up by Paris society, literary or otherwise. The witty boulevardier, journalist and chronicler Jean Lorrain was a well-known pederast but had to behave with extreme circumspection. Divorce was permitted by the legislation of the Republic and infidelity on the part of both sexes could be condoned or laughed at but only among a small, sophisticated set.