Christopher Thompson and Fiona Ratkoff, “'A Third Sex'

Bourgeois Women and the Bicycle in Fin de Siècle France” (1)

Gender and Bicyles -- Over View

When Sarah Bernhardt, who did not embody the traditional woman by the fireside, was asked in 1896 to evaluate the impact of women cyclists on society, she expressed great uneasiness.

I believe that the bicycle is in the process of transforming our customs more profoundly than is generally suspected. All these young women, all these girls who throw themselves into all-consuming space are renouncing an important part of the interior life, the life of the family. . . . Moral considerations should draw them away from it, and I believe that this outdoor life, for which the bicycle multiplies the occasions, can have dangerous and very serious consequences.

The perception that Sarah Bernhardt had of the consequences of female cycling at the end of  the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th was shared by a number of her compatriots, who associated this new activity with the recent claim by woman, particularly bourgeois women, to an unprecedented degree of liberty and of autonomy and with the rejection, even if it were to prove to be only temporary, of their traditional roles as wife and mother, as well as their desire to play with space and speed, which had up until then been monopolized by men.

the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th was shared by a number of her compatriots, who associated this new activity with the recent claim by woman, particularly bourgeois women, to an unprecedented degree of liberty and of autonomy and with the rejection, even if it were to prove to be only temporary, of their traditional roles as wife and mother, as well as their desire to play with space and speed, which had up until then been monopolized by men.

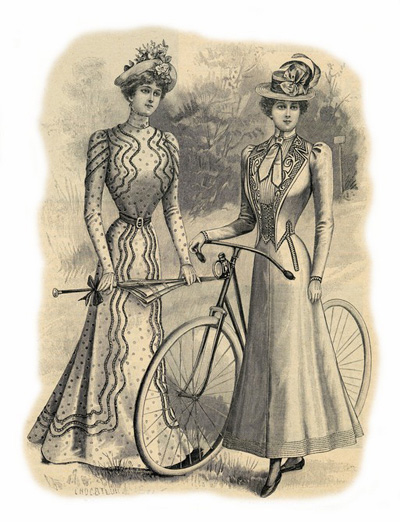

Bourgeois women, who looked for outfits better adapted to bicycle riding than their long skirts, petticoats, and corsets, adopted new clothing, pants and culottes, [“jupes-culottes”] inspired by men’s trousers. This appropriation of masculine clothing appeared as the symbol par excellence of a larger feminist attack against the traditional bourgeois system of representation of the sexes. Still more serious, the bicyle, this “technological partner of the new woman,” was suspected of becoming her new sexual partner. The doctors of the fin de siècle had heated debates about whether the act of pedaling ended in a form of masturbation which would lead women to seek sexual pleasure from their new machines, rather than in the conjugal bed. The obsessive fear of the French with the declining birth rate and its consequences for national security thus coincided with the insecurity of men in response to the emergence of female sexual autonomy. The combination formed a particularly explosive socio-cultural cocktail. The participation of women in new sports activities was particularly disturbing because it was believed in this period that the sole way for men to overcome their deficit in masculinity, so evident after the debacle of 1870, was on the sports field. The prospective of encountering their sisters and their wives on the same terrain was disconcerting for bourgeois men, who already felt that women had already disturbed the tradition representations and their implicit hierarchy. Obsessed with their presumed social, cultural, military, demographic, and “racial” decadence many Frenchmen saw in the person of the female cyclist the troubling confirmation of the degeneration of the nation.

In the end the bourgeois women on bicycles overcame most of the reservations and hostility that they provoked. Their triumph was due to their determination, but also to the support of a powerful ally, the cycle industry, which sought to exploit this new market of potential consumers. Female cyclists came to symbolize the new “reign of the consumer” (according to the expression of Charles Gide), a culture of mass consumption and of expanding leisure. . . .