Robert Nye,“The Culture of the Sword: Manliness and Fencing in the Third Republic” from Masculinity and Male Codes of Honor in Modern France (3)

The Roots of Honor in 19th Century France

The prestige of chivalric values may have ebbed for a few years after the democratic upheavals of 1848— 49 and the onset of the new Napoleonic dictatorship, but a discourse of honor emerged in the last half of the century that articulated the ideal of a reinvigorated republican manhood and the social and political values of a new democratic order. It may seem paradoxical that a cultural discourse born in a world of warring, unlettered nobles could retain its meaning in a democratic, industrial society, but as Norbert Elias indicated in The History of Manners, linguistic terms may fall into a state of sleep at certain times, but may "acquire a new existential value from a new social situation. They are recalled because something in the present state of society finds expression in the crystalization of the past embodied in the words." 14

The material conditions that supported a bourgeois discourse of honor also encouraged a cautious but inexorable strategy of class integration. From the Second Empire through the end of the century, the route for bourgeois social advance was much the same as it had been in the first half of the century. Industrialization and the modernization of the agricultural sector of the economy did not proceed fast enough to either sweep away traditional social and economic elites or guarantee the hegemony [i.e. political control] of the new productive classes. Even in the periods of most rapid industrial advance, archaic sectors of the economy were able to survive more or less intact, giving the French economy a mixed aspect. 15 . . .

There was no rapidly rising economic escalator in nineteenth-century France to whisk new men into social and political prominence. Social advance proceeded in the time-honored fashion by slow accumulations of social and educational capital, "synthesized" and "conditioned" by astute marital alliances. 17 Prejudices against marriages between individuals in the upper social ranks were rapidly crumbling. A popular etiquette book of the 1850s and 1860s advised both old and new elites to acknowledge the fact that, "since power these days is scattered throughout society, constituted in blood, in fortunes, and in rank, each may lay claim for himself the respect and the consideration he accords his neighbor." 18 Thus, social and marital relations with nobles continued to be valued by ambitious bourgeois, less perhaps for the economic or political power they wielded than for the cultural capital they possessed. ...

Although the "innateness" of the old nobility's "natural" taste was much admired, and emulated by the boldest of social climbers, bourgeois resentment of aristocratic snobbishness was still keenly felt. The inherent ambivalence of this relationship was played out, so to speak, in late nineteenth-century Parisian theater, which examined the tensions in the upper classes from every conceivable angle. Emile Augier, whose plays dominated the popular stage in the last half of the century, specialized in this theme. Despite his sympathy with the values and political goals of the liberal bourgeoisie, for Augier the distinctions of wealth meant little in the struggle for social supremacy. Manners and grandeur of outlook were everything; in this the middle classes had much to learn from their class rivals. Augier could not bring himself to make the following words, uttered by a noble personage in his Les Effrontes (1881), appear ridiculous: "Our orientation has a certain grandeur, our impertinance a certain grace. We have other convictions than our interest; in the end we are obliged to pay only one tax, which you others never pay, the blood tax." 20 . . .

It was France's crushing defeat in the 1870 war that raised a discourse of chivalry to higher levels of visibility. In its new year's day issue of 1871, the popular parisian newspaper, Le Petit journal, expressed the conviction that though French soldiers had been badly led, even betrayed by their commanders, the "honor of the ordinary fighting man emerged unblemished, as did his native, "sense of justice, frankness and generosity," and his "chivalric loyalty." 27 In the same year, but in a more pessimistic vein, Ernst Renan ruminated in his La Reforme intellectuelle et morale that France's predominantly roturier social order had somehow weakened her will to fight. Struggling to find a formula that would help encourage a national revival, Renan contrasted favorably France's essentially "democratic" honor with the class-bound honor of Prussia, but he hoped that his nation's egalitarian national identity could be reinfused with the positive qualities in the aristocratic and military spirit: the spirit of the honnete homme [respectable man]must be married to that of the galant homme [chivalrous man]. 28 . . .

Thus, despite the social and political differences that separated them, the principle factions of progressive bourgeois opinion in the second half of the century shared a nexus of common values— social integration (solidarity), patriotism, patriarchy— expressed in a discourse of masculine honor. One of the most popular spokemen for this set of themes was the academicien and playwright, Ernest LeGouve. Though of an advanced age by the 1870s, LeGouve continued to be an avid fencer; he encouraged the art, he wrote in 1872, because, "I would like our democracy to remain aristocratic in its manners and its sentiments, and nothing can'achieve that end more effectively than familiarity with the sword." 37 This cultural amalgamation would have the happy effect, LeGouve believed, of both harmonizing the classes in the new regime, and of improving the status of women.

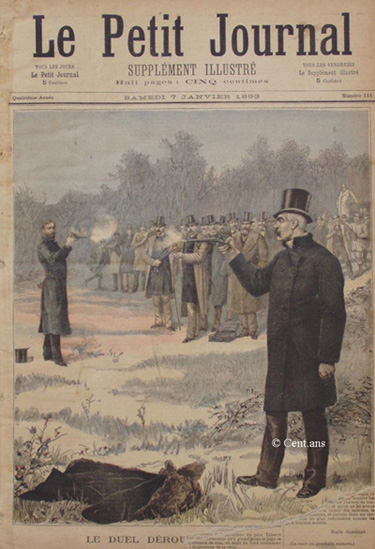

"The Duel Between Paul Déroulède and Georges Clémenceau," Petit Journal, 1893